Our History

History of Chinatown

Chinatown was the cradle of early Singapore's migrant population. The Chinatown or Kreta Ayer (water-carrying bullock carts) area has been the main landing area for our Chinese forebears who made the arduous crossing to Nanyang (S. E. Asia), via Singapore as the gateway. Between 1840 and 1900, two and a half million left South China to look for jobs.

In November 1822, Sir Stamford Raffles wrote to the Town Committee, directing attention to the 'proper allotment of the Native divisions of the town, and the first in importance of these is beyond doubt the Chinese'. 'From the number of Chinese already settled, and the peculiar attractions of the place for that industrious race, it may be presumed that they will always form by far the largest portion of the community. The whole therefore of that part of the town to the south west of the Singapore River is intended to be appropriated for their accommodation'.

Between 1871 and 1931, Singapore's population increased from less than 100,000 to over half a million, due to the huge influx of immigrants. The majority of early Chinese immigrants called 'sinkeh' who arrived in Singapore were indentured to a 'kongsi', and their services were engaged through a coolie agent or headman, otherwise known as a 'khektow'. Most came from 5 small regions in the southern provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, and Hainan. By the 1890s, these migrants were referred to as 'Huaqiao' or 'overseas Chinese'.

Chinatown was further divided into 'Greater town' (Kreta Ayer area) and 'Smaller town' (Kampong Glam, Rochor area), separated by the Singapore River.

Kreta Ayer refers to the water-carrying bullock carts that used to transport water to the residents in the area, as well as to water the streets to wash the roads.

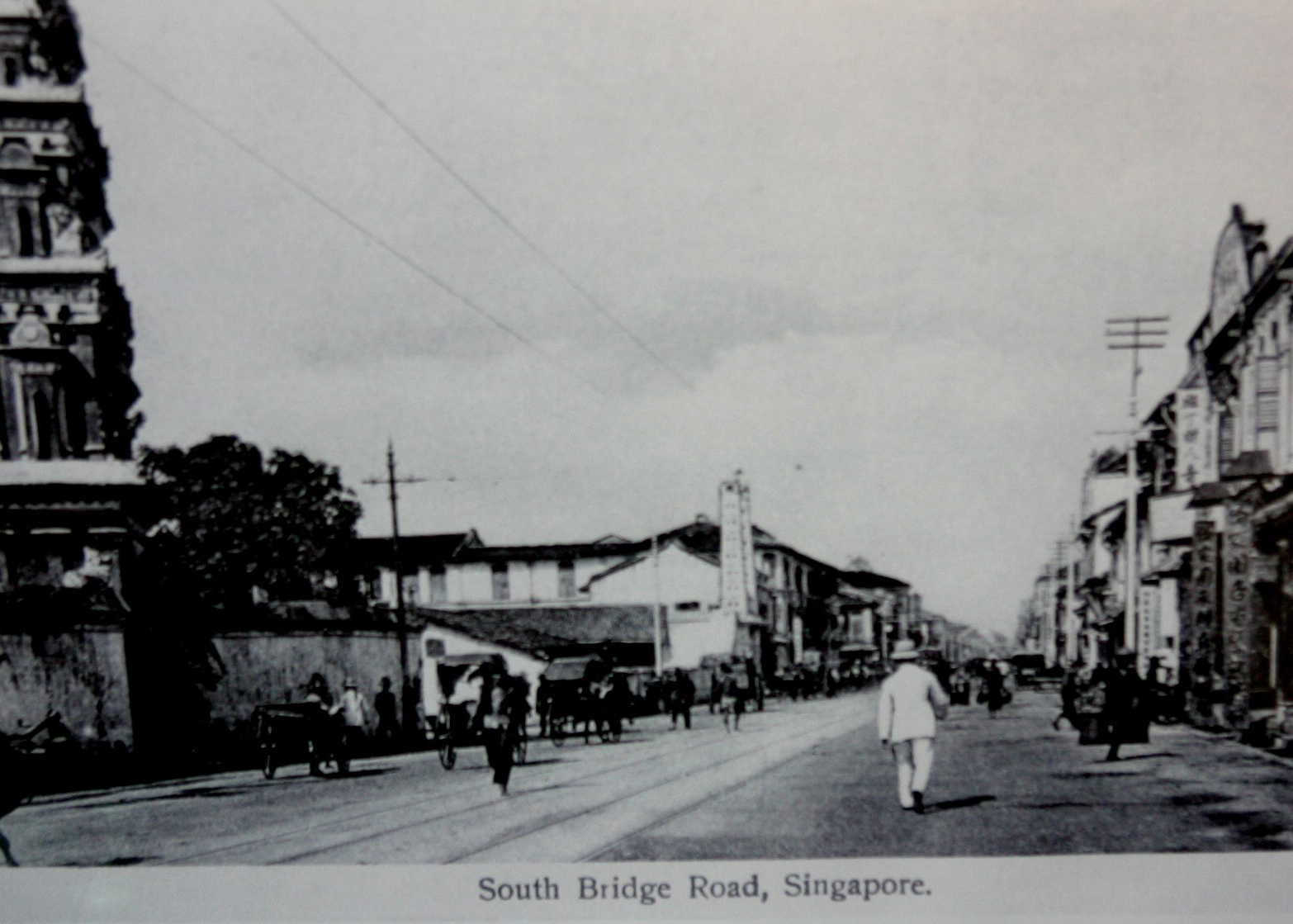

The original Kreta Ayer was the traditional Chinese precinct bounded by South Bridge Road, Kreta Ayer Road, New Bridge Road and Upper Cross Street. The land was leased or granted to the public in 1843 for the building of residential homes and shophouses. There have been only relatively little changes to the original buildings in the area.

Then complex and crowded, Chinatown was a mosaic of businesses, coolie quarters, bazaars, restaurants, theatres, shops and brothels. It was the most populated area then and no other place in Singapore can compare with it.

Many clan and mutual help associations were set up to help their clansmen settle down in the area. Many of the shophouses doubled as shop, warehouse, family quarters and workers dormitory.

Many of these shophouses display strong Fujianese, Teochew and Cantonese influence and the work of these craftsmen. These migrants from the various provinces congregated and settled in the following areas:

Hokkiens

Amoy Street, China Street, Telok Ayer Street, Hokien Street

Teochews

Boat Quay, North and South Canal Roads, Merchant Road, Carpenter Street, New Market Road, Upper Circular Road

Cantonese

Kreta Ayer Road, Temple Street, Pagoda Street, Mosque Street, Sago Street, Sago Lane

Hakkas

Upper Chin Chew Street, Upper Nankin Street and Upper Cross Street

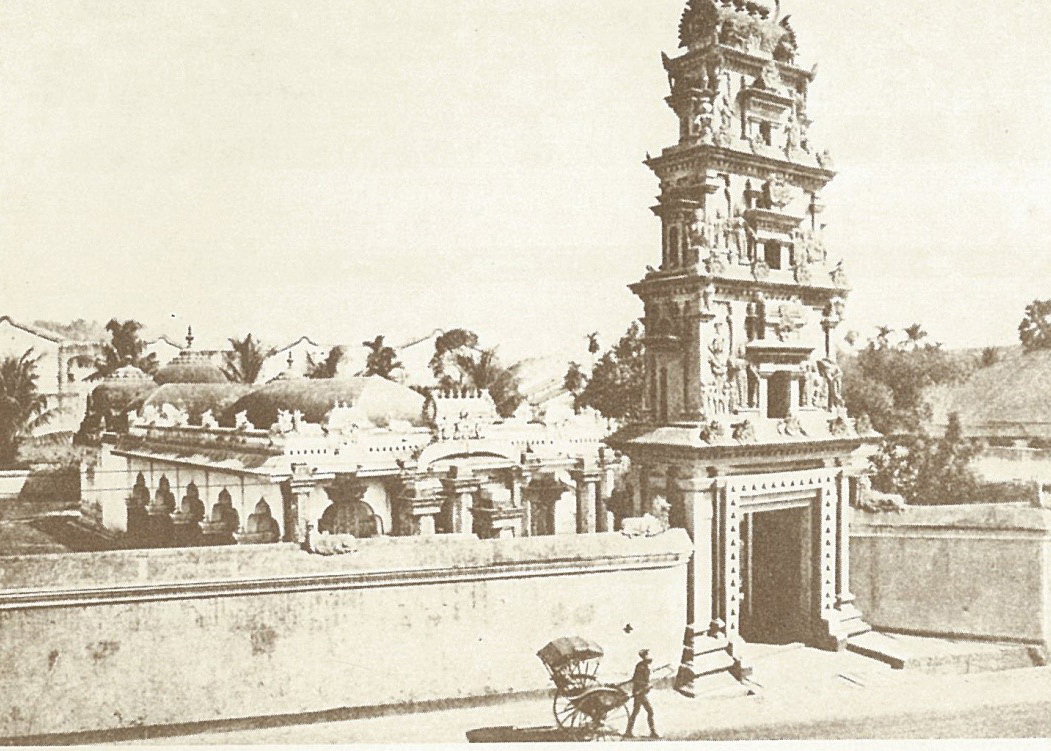

These various dialect groups also congregated at their respective temples:

Hokkiens

Thian Hock Keng Temple (1839) at Telok Ayer Street, Tiang Thye Temple (1849) at Upper Hokien Street

Teochews

Wak Hai Cheng Bio (1820) at Phillip Street

Cantonese

Fuk Tak Chi Temple at Telok Ayer Street

Quemoy

Poo Chay Bio Temple (1876) at Smith Street

These various dialet groups also formed clan associations as follows:

Hokkiens

Hokkien Huay Kuan (1860),

Teochews

Ngee Ann Kongsi (1845),

Cantonese

Ning Yueng Wui Kuan (1822),

Hakkas

Ying Fo Fui Kuan (1823),

These clan associations also set up schools for:

Hokkiens

Ai Tong School (1912), Chong Hock Girl's School (1915),

Cantonese

Yeung Ching School (1905),

In the 1880, the rickshaws was the dominant mode of transport and many new arriving migrants were rickshaw 'coolies'.

By the late 19th century, rickshaws had to contend with bullock carts, gharries, steam trams (1886) and electric trams (1905).

By 1920s, there were omnibuses (1929), trolley buses (1929), mosquito buses (1929), motor cars and lorries.

There was a small Indian community and traders with an Indian school at Upper Cross Street.

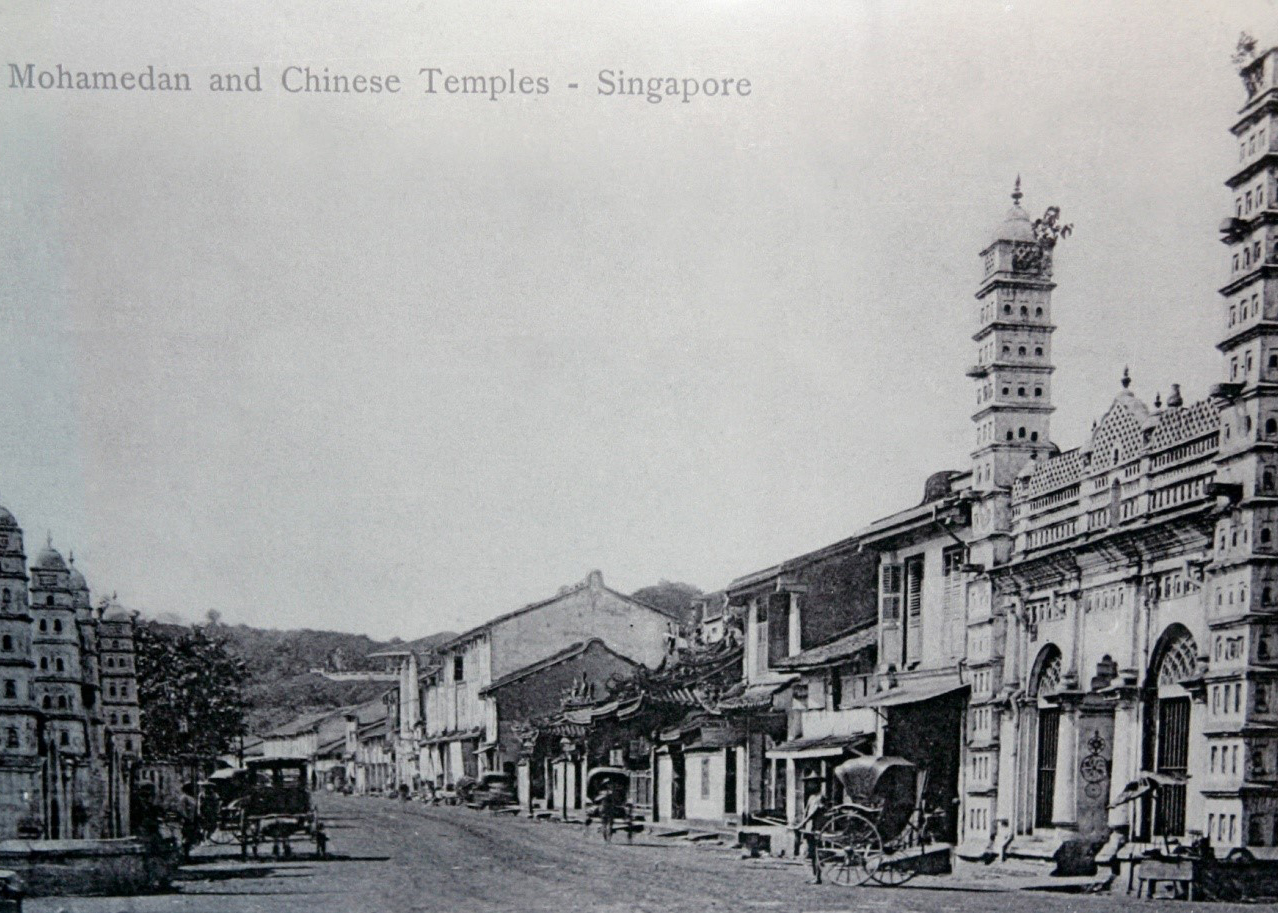

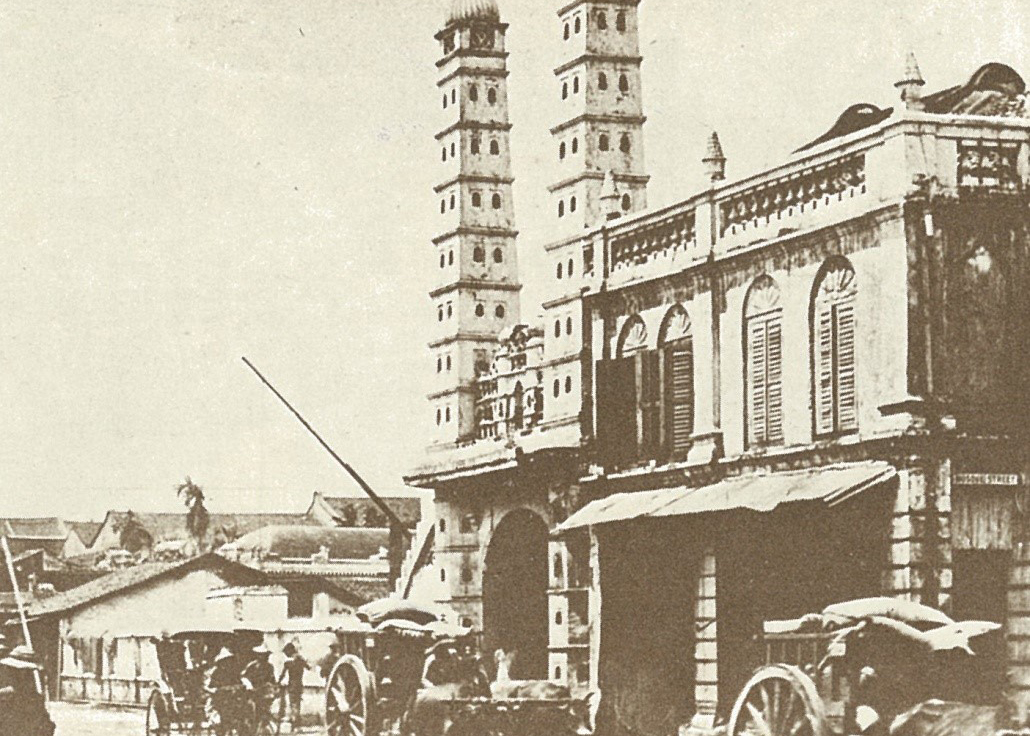

This stretch of South Bridge Road is also unique, as an example of Singapore's multi-racial and multi-religious community, with the Sri Mariamman Temple (1827), Jamae Mosque, or Masjid Chuliam(1830), Fairfield Methodist Church, and now Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum (2007).

Today, Chinatown remains the heart of the Chinese population with a revival of many of the traditional culture, arts and crafts. It is most crowded towards the Chinese New Year period where many locals will gather to buy Chinese new year goodies and revel in the various festivities.

Bibliography:

- Chinatown, an album of a Singapore community, Times Books International, Archives and Oral History Department, 1983, ISBN 9971 65 117 3

- Kreta Ayer, Faces and Voices, Kreta Ayer Citizens’ Consultative Committee, 1993, ISBN 981-3002-73-5

- Tanjong Pagar, Singapore’s Cradle of Development, Tanjong Pagar Constituency, Landmark Books, 1989, ISBN 981-3002-27-1

- Singapore, A Pictorial History 1819 – 2000, Gretchen Liu, National Heritage Board & Editions Didier Millet, 1999, ISBN 13 978-981-3018-81-5, pages 136 – 145, 210 – 211

- Singapore, A Biography, Mark Ravinder Frost & Yu-Mei Balasingamchow, Editions Didier Millet & National Museum of Singapore, 2009, ISBN 978-981-4217-62-0, pages 149 – 175

- A History of Modern Singapore 1819 – 2005, C. M. Turnbull, NUS Press, National University of Singapore, 2009, ISBN 978-9971-69-343-5

- Chinatown, Rhythm & Blues, Khong Swee Lin & Carl-Bernd Kaehlig, Times Media Pte Ltd, 2001, ISBN 981-232-094-6

- A Journey Through Singapore, Travellers’ impressions of time gone by, Reena Singh, Landmark Books, 1995, ISBN 981-3002-97-2